Families of missing black Americans fight for media, police to focus on their loved ones’ cases

The National Center for Missing And Exploited Children based in Washington D.C. is the most important agency in the country when it comes to tackling missing persons cases, and its director says that when it comes to finding missing Americans, there’s a color problem.

Robert Lowery, who leads the center, says that roughly 800,000 Americans go missing each year.

“About 60% of the reports that we see here in the U.S. that go in those databases are people of color,” he said. “I think it really breaks a lot of commonly held thoughts on who are really the missing children in the U.S.”

Missing black Americans are over-represented in the total number of missing people in the U.S. Despite making up only 13% of the total U.S. population, more than 30% of all missing persons were black in 2018, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Only about one-fifth of these cases are covered by the news, according to an analysis published in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology.

Black families searching for missing relatives say that their missing loved ones are more likely to be labeled as runaways, and that they are somehow not worth the focus of the police or the media.

Paula Cosey Hill says it happened to her.

Her daughter Shemika Cosey disappeared without a trace just a few days after Christmas in 2008.

“On December the 28th, that was the last day I had seen her, and it was a normal day,” Hill told ABC News.

Hill said her daughter had been watching movies with her cousins on that day, but when everyone woke up the next morning, she was gone.

At the time, police believed that because the door to the family’s home just outside of St. Louis, Missouri, was unlocked, Shemika must have run away. For this reason, they ultimately chose not to launch a search for the teen.

“They not doing anything, because they think she [had] gone on her own,” Hill recalled tearfully. “I just didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know who to turn to.”

Local news anchor and reporter Shawndrea Thomas produces a podcast that documents forgotten cases of missing black Americans called “Intrigued Full Effect.”

Thomas told ABC News that “Shemika Cosey’s story was different in that she just vanished without a trace.”

“Her belongings, her overnight bag were still left on the counter in the house and she was never seen again,” she explained.

Thomas agrees that police and the press often dismiss black cases as runaways.

“It has been difficult to get some of these stories told as it comes to missing people of color, cold cases involving people of color, and I felt like if I can do my part as far as having this podcast, I can tell any story I want about whoever I want, however I want for however long I want,” Thomas explained.

Major Art Jackson, a black police officer at the Berkeley Police Station that investigated Cosey’s case, said “there was no evidence to support a physical search.”

“This is one of the hardest things to investigate, is a missing person, especially if a person is missing with, like I said, with no signs of anything. Just voluntarily walks away,” Jackson said. “If a person is missing, they’ve been kidnapped or anything like that, you’re going to have signs of struggle, you’re going to have things to go by to help you put that piece of the puzzle together. So…in reality, sometimes law enforcement and sometimes media [will think], ‘Hey, that person did it voluntarily. So that’s on them.'”

In the past few years, there have been dozens of missing persons cases with massive and hopeful search efforts on the ground and in the news. The common thread among these cases is that those who are missing are white.

On the same day that 17-year-old Caitlyn Frisina went missing from Florida in 2017, 14-year-old Yaniya Jovon Carter went missing under similar circumstances just outside Atlanta. Yaniya, however, did not get half the attention from the media or the police that Caitlyn did.

Fortunately, both girls were found safe. Frisina was found with a 27-year-old soccer coach and family friend who was sentenced to 18 months in jail for taking the child away, and is now serving time. Carter was found with what police say was a 19-year-old boyfriend. He was not charged.

When Mariah Woods, a 3-year-old white girl, went missing in Jacksonville, North Carolina, at least two black children in a neighboring county were also missing — but only Mariah had more than 700 people searching on foot and coverage in the nation’s news media.

Because the numbers of missing black Americans are so high, it’s hard to find an instance where a black case hasn’t been ignored.

Natalie and Derrica Wilson run an online search agency called the Black and Missing Foundation, which helps search specifically for missing black and Hispanic children.

“There are so many families of color who are desperately searching for their missing loved one and they are just asking for just one second or a couple of seconds of media coverage and it can change the narrative for them,” Natalie Wilson said.

Derrica Wilson added, “We also understand that the decision makers don’t look like us. And so these cases are not sensitive enough where they want to air it.”

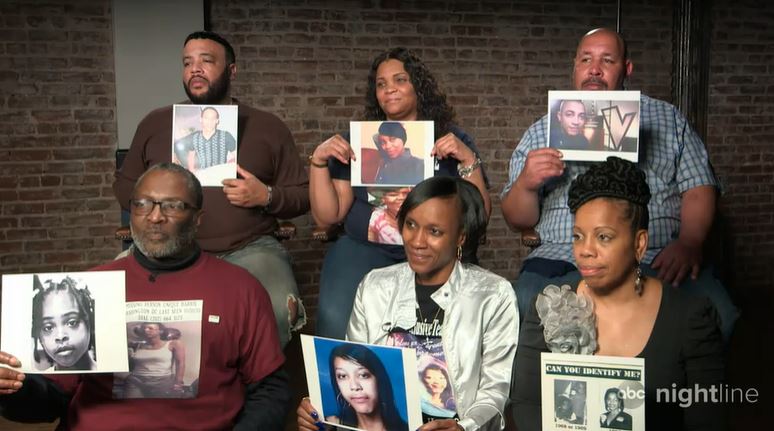

Parents and loved ones of missing black children met with ABC News in Washington D.C., where they said that they would take a fraction of the compassion and attention that has gone to the families of Natalee Holloway, Elizabeth Smart, Laci Peterson and so many others.

Terrence Woods, whose son Terrence Woods Jr. is missing, called it depressing to see white kids in the majority of missing children stories covered by black reporters.

“I know how many missing people of color that are missing,” Woods said. “I would say, ‘Well, [does] he do his homework to talk about us?'”

Toni Jacobs, whose daughter Keeshae Jacobs is missing, added that “it pissed me off to see you reporting on somebody else’s child other than mine.”

“I had to fight to get mine on local news, and this person’s on national news with the F.B.I. overnight,” Jacobs said. “I’m tired and I’m frustrated and I’m pissed.”

This group wants America to take a greater interest in the names of their missing loved ones: Unique Harris, who has been missing since October 2010; Christian Muse, who has been missing since July 2012; Relisha Rudd, who has been missing since March 2014; Keeshae Jacobs who’s been missing since September 2016; and Terrence Woods Jr., who went missing last October.

Valencia Harris said she misses her daughter Unique’s “jovial attitude.”

“She always could just walk in a room and brighten up the room, and you know, she kept me laughing even when I didn’t wanna laugh,” her mom said.

Toni Jacobs said her daughter Keeshae “was 21 when she went missing.”

“But she was still my baby. She’s the one that we used to have movie nights and she’d lay up in the bed with me, and we’ll watch movies and eat popcorn,” she recalled.

Michael Muse said he has gone through a difficult cycle of emotions since his son’s disappearance. “I’ll have dreams about Christian, and in these dreams I will be boo-hooing, crying, you know, in my dream. But then I’ll wake up [with] that same feeling of sorrow and no physical tears are coming out,” he said.

“My son, Terrence, he was my best friend,” Terrence Woods said. “And this just recently happened so, I mean, every Christmas he would put up the Christmas tree. So this Christmas it was, like, really different, you know? And he was with 11 other people, but he’s the only one that went missing without a physical trace.”

“It just hit me like a gut shot,” he continued.

“I don’t even like walking down the hall going toward his room,” Woods said. “And the sheriff’s department, nobody is really helping out.”

Woods Jr. went missing last fall in the forests of Orogrande, Idaho, where he was shooting a documentary.

Police ended the search within a week and said “no leads were obtained and no signs of Mr. Woods” had been “located in the search area.” Authorities have said they are continuing to monitor the situation.

Since that time, however, Woods said police have told him nothing further.

Unlike other missing persons cases, where FBI agents often appear the next day, federal agents confirmed to ABC News that they never joined the search, saying that “local authorities have primary jurisdiction here and we get involved at their request. We have not received a request for assistance.”

“I think a lot of people get the misunderstanding that we immediately get help from the police department,” Valencia Harris said. “That’s not the case.”

But a small ray of hope shines on the horizon, and it comes from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which has brought in representatives from local law enforcement and news departments in the Washington D.C. area to help point out the differences in search effort.

“We’ve initiated a minority children initiative here to examine that very question,” Lowery said. “Those large scale searches, in our experience, have been predominantly for Caucasian children. And [for] reasons that we don’t always understand.”

The families, whose voices are filled with frustration, console each other often.

“I’ma tell you straight up,” Toni Jacobs told the group. “Don’t give up. Like you said, don’t accept nothing nobody say. Can’t nobody tell you no. Can’t nobody tell you no, and you keep fighting until you can’t fight no more.”

Harris added, “Remember, that’s your child, and nobody — and I mean nobody — is gonna fight for your child like you do.”

“Everything in my heart is telling me that Keeshae is alive,” Jacobs said. “But I believe she is coming home to me.”

Hill shared a similar optimism to this group of parents, and went so far as to submit DNA samples for herself and her other two children to a national registry in hopes of one day finding a match to Shemika.

“I still have hope,” Hill said. “I still have hope that one day, I’m gonna find my child.”

If you have any information about Shemika Cosey, Unique Harris; Christian Muse, Relisha Rudd, Keeshae Jacobs, or Terrance Woods Jr., please call the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 1-800-THE-LOST / 1-800-843-5678.