Why the legacy of American slavery endures after more than 400 years

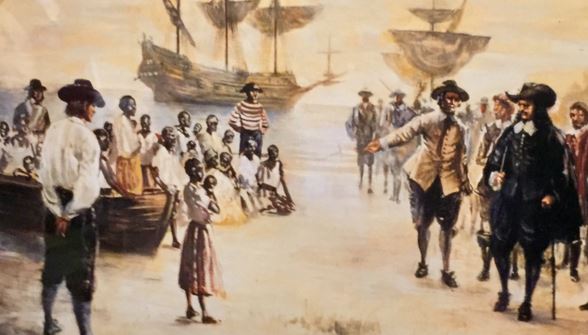

A year before the Pilgrims made their famed journey to New England, signing the “Mayflower Compact” and thus inaugurating so many of the myths that we believe about our democratic origins, a very different ship disembarked in that older English colony to the south, Jamestown. Aug. 20, 1619, marked the arrival of 20 enslaved Africans in English North America, “bought for victuale … at the best and easyest rate they could” as recorded by the tobacco planter John Rolfe (Pocahontas’s husband), some 15 months before the Mayflower supposedly landed near Plymouth Rock.

This anniversary affords us an opportunity to think about American origins; both what we choose to remember and what we choose to forget. Every schoolchild has heard of the Mayflower, but not of the White Lion and the Treasurer, ships that kidnapped Africans. We glorify the Pilgrims as models of liberty, and the Virginians as captains of industriousness, but as always, the reality was more complicated. The histories of these two regions were intertwined with the dark underbelly of human exploitation and bondage, which Jamestown established a year before the Pilgrims arrived.

Too often, America’s history of slavery, which is deeply entangled with the economics of the nation, is taught and remembered as something antique, forgotten and regional. But so enduring has the legacy of slavery been and so scant has been our actual reckoning concerning this evil that we are obligated to look more closely at what Jamestown and Plymouth mean, and why we should remember them together.

The story of the enslaved Africans and their arrival in Jamestown has long been recounted as a counterpoint to the story of the landing of Pilgrims in Plymouth. Historian Jill Lepore compares the relationship between the two colonies in subsequent American imaginings as being a sort of “Cain-and-Abel, founding moment.” An American abolitionist writing in 1857 quoted by Lepore exclaimed that as regards the colonies, “Here are two ideas, Liberty and Slavery — planted at about the same time, in the virgin soil of the new continent; the one in the North, the other in the South. They are deadly foes.”

Southern apologists interpreted those two landing dates in a different way. George Fitzhugh would compare Massachusetts and Virginia in 1860, declaring that the coming war was “between those who believe in the past, in history, in human experience, in the Bible, in human nature, and those who … foolishly, rashly, and profanely attempt to ‘expel human nature,’ to bring about a millennium.” For southerners such as Fitzhugh, New England Puritanism had strayed far from its Protestant roots, embracing what critics saw as the moralizing liberalism of denominations such as Unitarianism and cultural movements such as Transcendentalism. For Fitzhugh and those like him, these “heretical” children of Puritanism now threatened what he saw as both his economic livelihood and his “right” to hold other humans in bondage.

But the kidnapped people who were sold in Virginia 400 years ago weren’t symbols, they were women and men. They were real people who’d previously lived their lives as inhabitants of the African kingdom of Ndongo and were forcibly brought to labor in Jamestown. A 1624 census in Jamestown shows the otherwise anonymous Antoney and Isabella as the parents of William Tucker, the first African American to be born on these shores. Any memory of the early origins of America must center the experiences of people such as Tucker. And remembering the bondage of actual individuals reveals the shared similarities between Virginia and New England that bound the two parts of Colonial America together.

The slave trade was a driving force in the colonization of what became the United States, and indeed the rest of the Americas as well; it preceded English settlement and transcended regional difference. This didn’t just start when “20 and odd Negroes” were forcibly brought to Virginia from Angola in 1619. The transatlantic slave trade had already been operating in Spanish and Portuguese colonies of the Americas for more than a century, and indeed it would exist for more than a century in the New England colonies as well, if not to the same extent as it did in the south. To remember Jamestown as the origin of American slavery is to forget its earlier instances, and to ignore the presence of slavery outside of the south.

True that Massachusetts, in part because of its Puritan origins, would ultimately become the cradle of American abolitionism. But in its first century-and-a-half, slavery initially found home in Plymouth, Boston and Salem as surely as in Jamestown, Charleston and Wilmington. In the early American colonies, both Massachusetts and Virginia relied on the exploitation of enslaved people, as well as the brutal suppression and ethnic cleansing of the indigenous population. Both colonies would countenance slavery, even as it was eventually abolished in Massachusetts for economic reasons as much as moral ones.

But, bringing Jamestown and Plymouth’s legacy of slavery into our shared memory of the nation’s origin is essential. After all, 246 years of slavery dominate the American story, in contrast to only 154 years of emancipation. To simply see those two colonies as a Cain and Abel is to forget the legacies of slavery that taint both, and which indeed still taint us today. It is appealing to imagine that the American story is one of independence and freedom, with only occasional exceptions to that. But we must correct ourselves by keeping those twined events in mind, for we’re descendants of both the Mayflower and the White Lion, citizens of both Plymouth and Jamestown. If we celebrate what we imagine the Mayflower to represent, while burying what the White Lion does, then we’re exonerating our history at the expense of the truth.