Hip-hop has been standing up for Black lives for decades: 15 songs and why they matter

From 1982 to 2020, here are 15 memorable records and lyrics rooted in protest.

Decades before “Black Lives Matter” became a global hashtag touted by celebrities and leading politicians, hip-hop artists were profiled, targeted and vilified for broadcasting those same systemic injustices that plagued Black America — a reality that for decades was shut out of mainstream media.

In the early 1970s when hip-hop was born in the Bronx, New York, poverty and brutality plagued Black communities, but discussions on race and racism in America were considered taboo and, in the media, the Black experience was stigmatized and suppressed.

Detroit rapper and activist Royce da 5’9” said that amid this void, hip-hop artists in the ’80s “pushed the envelope in terms of exercising their First Amendment right” and became “the voice of the streets.”

“It was that voice that America couldn’t control … it was that voice of the streets that they didn’t know what the next line is gonna be and that scared them,” he told ABC News. “Because we spoke our own unapologetic truth. We spoke about environments that were overlooked, that didn’t have a voice, you know, that didn’t have a say, that didn’t have pretty much anything.”

Compton, California, rapper Day Sulan, who was arrested last month during a police brutality protest, said that even when the debate on racism in America is no longer in the national spotlight, it will always be at the center of hip-hop.

“If Black lives matter, hip-hop is Black people, it’s something we started, something we originated so it’s not just a hashtag,” she told ABC News. “Hip-hop is gonna continue that movement and it’s never gonna stop because that’s what we are, that’s what we stand for.”

From legends and icons to underground trailblazers, hip-hop artists weaved a rich, uniquely American art form that not only documents inequities and racism in America, but the movements and leaders that rose up in the face of oppression.

From 1982 to 2020, here are 15 memorable records and lyrics that reflect hip-hop’s roots in activism:

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, “The Message” (1982)

“A child is born with no state of mind/ Blind to the ways of mankind/ God is smiling on you, but he’s frowning too/ Because only God knows what you’ll go through/ You’ll grow in the ghetto living second-rate/ And your eyes will sing a song of deep hate.”

When “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five was released in 1982, Chuck D, who would become a hip-hop icon himself, was only a teenager. But the future Public Enemy emcee told ABC News that he was “stunned by it.”

“When ‘The Message’ came out, there was nothing like it. Nothing. Ever. Like that. So the change, it came overnight,” Chuck D said. “It was a non-danceable record. That’s the thing that blew a lot of people away was like, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five made some very danceable hip-hop music, but when that record came out, it totally changed everything.”

Asked what the title of the song meant to him, Chuck D said, “It means pay attention to the words of hip-hop instead of just the beat.”

“The Message,” which features only Duke Bootee and Melle Mel from the group, was the most prominent hip-hop song at the time to feature social commentary. In the last verse, Melle tells a gut-wrenching story about a young man who drops out of school, ends up in jail and dies by suicide after getting repeatedly raped behind bars.

The song was named in 2017 by Rolling Stone as the best hip-hop record of all time and has been archived by the Library of Congress.

NWA, “F— Tha Police” (1988)

“F— the police comin’ straight from the underground/ A young n—- got it bad ’cause I’m brown/ And not the other color so police think/ They have the authority to kill a minority.”

When NWA released its debut album, “Straight Outta Compton,” in 1988, featuring songs like “Gangsta Gangsta,” “Straight Outta Compton” and “F— the Police” — a bombastic anthem against police brutality — white America was outraged.

The Parents Music Resource Center launched a public campaign against the group and its use of profanity, while the FBI targeted and investigated its members — Eazy-E, Ice Cube, Arabian Prince, DJ Yella, Dr. Dre and MC Ren.

But for Black Americans who experienced the disenfranchisement and brutalization of their communities, songs like “F— the Police” were “liberating,” Royce da 5’9” said.

“To me like, as a young kid, I was just like, ‘Wow, they curse really good. They curse better than my dad, they say ‘F— the police,’ that’s crazy,'” he added. “I didn’t know you can get on a song and say that, you know, right. It was like, almost liberating — liberating in a way to a young kid who isn’t used to really having a voice or being heard or people or feeling like anything about him matters.”

In 2017, NWA’s “Straight Outta Compton” was archived by the Library of Congress.

KRS-One, “You Must Learn” (1989)

“Teach the student what needs to be taught/ ‘Cause Black and white kids both take shorts/ When one doesn’t know about the other ones’ culture/ Ignorance swoops down like a vulture.”

Arguably one of the most successful politically and socially conscious emcees of all time, KRS-One is a teacher. For decades, the Bronx native and standing member of Boogie Down Productions, has used his voice to educate — eloquently rhyming about social ills like police brutality, poverty, lack of education and racism.

“When I came out with my music at that time there was a major crack cocaine epidemic in New York,” the Bronx rapper told CNN in 2015. “The music that I would do would speak to these issues, would speak to why are we living in these conditions. It’s like no one has any power to lift us from these conditions.”

“You Must Learn” provides a history lesson in religion, war and education, as well as the rich contributions of Africans Americans in this country.

Public Enemy, “Fight the Power” (1989)

“Our freedom of speech is freedom or death/ We got to fight the powers that be.”

When film director Spike Lee approached Public Enemy to write a song for his upcoming movie, “Do The Right Thing,” Chuck D named it after a 1974 protest song he had heard as a child — “Fight the Power” by the R&B, soul and funk group The Isley Brothers.

“‘Fight the Power’ is very important because that’s the song that influenced me. When I was 14 years old, 15 years old, that record came out and it resonated with me,” Chuck D said. “And it was the first record I heard they had a curse word. … And that was riveting in itself and had a lot of meaning and youth rebellion in the song.”

But according to Chuck D, the song would not have been as successful had it not been featured in the film.

“We had allies who are just as rebellious,” the rapper said, crediting Lee with the song’s success. “‘Fight the Power’ really doesn’t exist in the same way if you don’t have a lot of Black movies, and everybody went to see this one Black movie by a Black filmmaker — Spike Lee … so that right there just dissolved a lot of the difficulties. It might have had more difficulty if it was a standalone song on its own trying to penetrate the marketplace; we would have found resistance.”

The song was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2018 and music by Public Enemy’s 1990 album “Fear of a Black Planet,” which includes the song, was archived by the Library of Congress in 2004.

Queen Latifah, “U.N.I.T.Y.” (1993)

“I walked past these dudes when they passed me/ One of ’em felt my booty, he was nasty/ I turned around red, somebody was catching’ the wrath/ Then the little one said, ‘Ha ha, yeah me, b—-,’ and laughed.”

In a male-dominated industry riddled with misogyny, many female emcees work tirelessly to carve out a space.

Before becoming a prominent Hollywood actress and producer, Queen Latifah demanded respect and asserted herself as hip-hop royalty. “U.N.I.T.Y.” challenged everyone to make room for the queen, and gave women permission to be powerful, graceful and strong, and to expand, not shrink.

“U.N.I.T.Y.” won the Grammy for best solo rap performance in 1994.

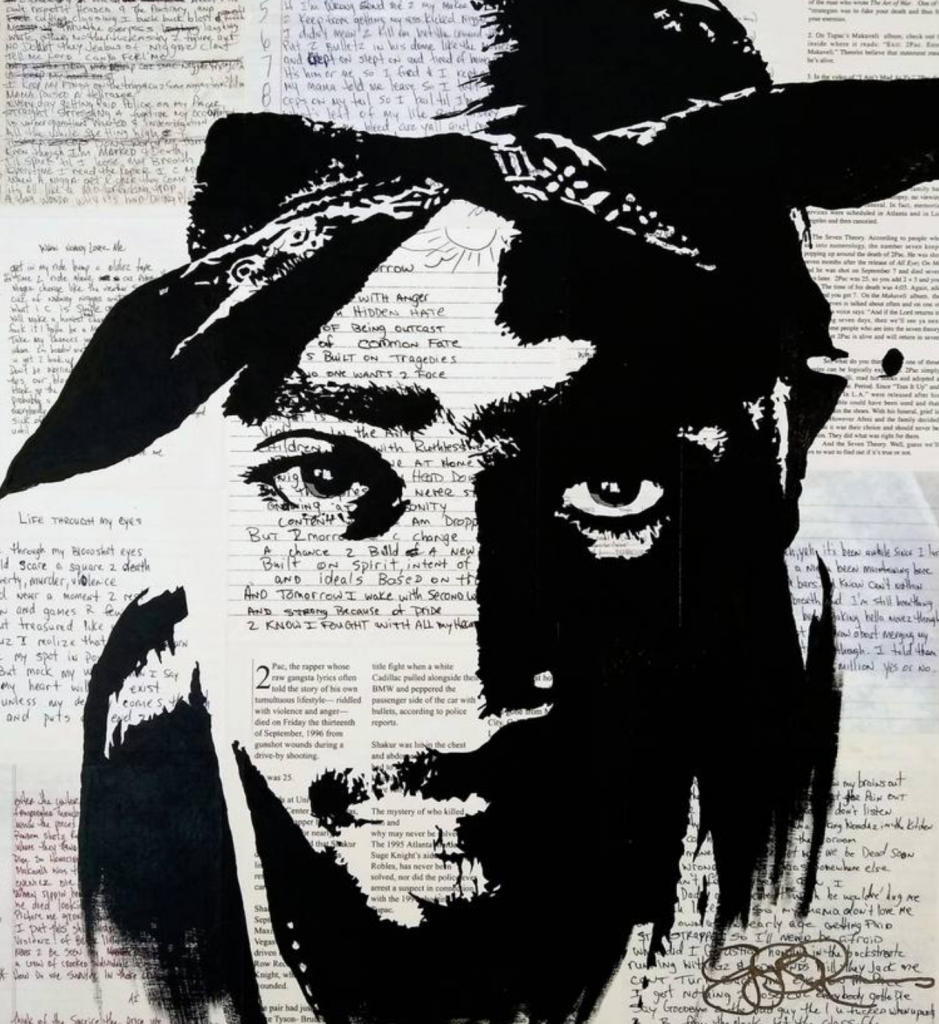

Tupac, “Me Against the World” (1995)

“The question I wonder is after death, after my last breath/ When will I finally get to rest through this oppression?/ They punish the people that’s asking questions/ And those that possess steal from the ones without possessions.”

The life of iconic rapper Tupac Shakur can be described as a lesson in politics, justice and Black activism. Seen as both a hero and a villain, Tupac was one of hip-hop’s most powerful and outspoken voices for social justice and radical change.

Sulan said that Tupac is the “No. 1 influence for why I am the activist I am.”

“He really helped a lot of my mindset, my growing up watching his interviews,” the 22-year-old artist said. “He was just one of the people that really used his voice for the right reason to show people like what real is like. … He said, ‘I’m gonna spark the mind of somebody who’s gonna change the world if I don’t,’ and he really did.”

Tupac was locked in a prison cell when “Me Against The World,” one of his most personal and introspective albums, was released. The song of the same title was a soulful, poetic display of raw, honest and dark lyrics rooted in vulnerability and trauma.

Nas, “One Mic” (2002)

“Police watch us, roll up and try knockin’ us/ One knee I ducked, could it be my time is up?/ But my luck, I got up, the cop shot again/ Bus stop, glass burst, a fiend drops his Heineken.”

The multi-platinum Queensbridge, New York, native is a powerful narrator who masterfully strings together street tales of desperate neighborhoods.

In a world of abundance and overindulging, “One Mic” demonstrates the power of one: one mic, one prayer, one breath. Nas’ powerful and passionate delivery is a cry for immediate action, ending each refrain with “the time is now.”

“‘One Mic’ is how I’ve been feeling,” Nas told MTV in 2002. “‘One Mic’ has been on my mind for a long time. I knew that people weren’t being for real and truthful from the heart with the music that was coming out. ‘One Mic’ represents my every emotion, everything that’s in my mind.”

Kanye West featuring Jay Z and J Ivy, “Never Let Me Down” (2004)

“Racism still alive, they just be concealin’ it.”

In his debut album, “The College Dropout,” Kanye West teamed up with Jay Z, spoken word poet J Ivy and Tracie Spencer on vocals for a melodic and poetic song about being true to yourself and to your roots.

Jay Z raps about being true to himself and to his fans from day one in his music and West raps about his family’s history in the civil rights fight and how this has become an intrinsic part of him: “I get down for my grandfather who took my mama/ Made her sit in that seat where white folks ain’t want us to eat/ At the tender age of 6, she was arrested for the sit-ins/ And with that in my blood I was born to be different.”

The song, which was originally recorded for Jay Z’s seventh studio album, “The Blueprint²: The Gift & The Curse,” ends with a powerful delivery by J Ivy of his poem, “Never Let Me Down.”

Talib Kweli, “Eat to Live” (2007)

“Anyway, grandma say Jesus will be here any day/ Good — ’cause with nothing to eat it’s gettin’ hard to pray.”

Talib Kweli has built his career on exposing injustice, racism and rampant systemic flaws. “Eat to Live” is an important song that addresses food deserts, malnutrition and the consumption of non-life-giving foods.

Science has linked poor eating habits with health conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes, which are both prevalent in Black communities.

This issue has been brought to light amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately been killing Black Americans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals who suffer from health conditions like obesity and diabetes often experience worse outcomes when contracting the virus.

Meek Mill, “Dreams and Nightmares” (2012)

“I used to pray for times like this, to rhyme like this/ So I had to grind like that to shine like this/ And the matter of time I spent on some locked-up s—/ In the back of the paddy wagon, cuffs locked on wrists/ Seen my dreams unfold, nightmares come true.”

Before the Philadelphia rapper rose to the national spotlight in 2017 as one of the most prominent criminal justice reform advocates, Meek Mill recounted his struggles and his triumphs in “Dreams and Nightmares,” the first track on his 2012 album bearing the same title.

In the first part, “Dreams,” Mill recounts his rise in the rap game through reflective lyrics, but halfway through, his tone becomes angry and bombastic depicting his “nightmares.”

When the rapper was sentenced to two to four years in prison in November 2017 after a pair of arrests that violated his probation from a 2008 gun and drug case (including popping a wheelie on a motorcycle), his case sparked outrage among criminal justice reform advocates and reinvigorated a national debate on mass incarceration.

While he was in prison, “Dreams and Nightmares” became an anthem of the #FreeMeekMill movement. The song was blasted by protesters and was chosen by the Philadelphia Eagles as their anthem during Super Bowl Lll to show solidarity with the rapper.

Lauryn Hill, “Black Rage” (2012, re-released in 2014)

“Black rage is founded on blatant denial/ Squeezing economics, subsistence survival/ Deafening silence and social control/ Black rage is founded on wounds in the soul.”

In 1961, famed author and activist James Baldwin said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time.”

More than 50 years later, in 2012, musical genius Lauryn Hill, whose debut album was the first hip-hop album to earn a Grammy for album of the year, affirmed Baldwin’s sentiment with “Black Rage.”

The poignant song was re-released among the Ferguson, Missouri, protests in 2014, and the themes remain today. The unaddressed inequities that resurface decade after decade is another example of why Black rage exists.

Kendrick Lamar, “Alright” (2015)

“Uh, and when I wake up/ I recognize you’re looking at me for the pay cut/ But homicide be looking at you from the face down.”

Soulful and introspective with an ever-present political charge, Kendrick Lamar has mastered Black storytelling in rap music.

“Alright” is a powerful, poetic glimpse at the Black experience, one that transcends pain and oppression. The message is hope and faith, and while the story’s imagery is dark, light emerges through Kendrick’s courage, beauty and pride.

“Alright” won a Grammy for best rap song at the 2016 awards and Lamar’s “To Pimp a Butterfly,” which features the song, won a Grammy in the best rap album category that year.

Meek Mill featuring Jay Z and Rick Ross, “What’s Free” (2018)

“Tryna’ fix the system and the way that they designed it/ I think they want me silenced/ Oh, say you can see, I don’t feel like I’m free.”

Meek Mill enlisted industry powerhouse and billionaire Jay-Z to discuss modern-day freedom on this track.

While Meek draws on his personal experiences and hardships with the judicial system, Jay talks about narrowly escaping the system, building wealth and civil liberties.

Last year, the two rappers, who have used their fame, access and fortune to affect change, co-founded Reform Alliance, an organization committed to prison reform.

Rapsody, “Nina” (2019)

“I’m from the back woods where Nina would/ Sing about the life we should lead/ A new dawn, another deed, I try to do some good/ I felt more damned than Mississippi was.”

Rapsody’s “Nina” is a tribute to Nina Simone and begins with the legendary singer’s rendition of “Strange Fruit” – a poem by Abel Meeropol published in 1937 protesting the lynching of Black Americans.

The Grammy-nominated North Carolina rapper references Simone’s first protest anthem, “Mississippi Goddamn,” a response to the 1963 assassination of American civil rights activist Medgar Evers in Mississippi amid his fight against Jim Crow laws.

“Nina” is one of the songs on Rapsody’s album “Eve” — an ode to the history of the civil rights movement and the Black women who broke barriers, including Queen Latifah, Aaliyah and Maya Angelou.

“There’s a beauty and a strength that all of them have because to break the barriers that they had to do, you had to be unwavering, you had to have this undeniable, undying fight within you,” Rapsody told ABC News in August 2019.

Lil Baby, “Bigger Picture” (2020)

“F—ed up, I seen what I seen/ I guess that mean hold him down if he say he can’t breathe/ It’s too many mothers that’s grieving/ They killing us for no reason.”

Politically conscious rappers aren’t nearly as popular today, but the message always finds its way to the music.

Popular rapper Lil Baby released “Bigger Picture” after the recent death of George Floyd and the racial protests that followed. The anthem, which demands a stop to police brutality, garnered more than 65 million audio and video streams in its first two weeks, according to Nielsen Music.

In an Instagram post, Lil Baby said that the proceeds from the song will benefit organizations like the National Association of Black Journalists, the attorneys for the family of Breonna Taylor, who died at the hands of Louisville police, the Black Lives Matter movement and The Bail Project.