The nation’s economic recovery is still unequal for Black workers

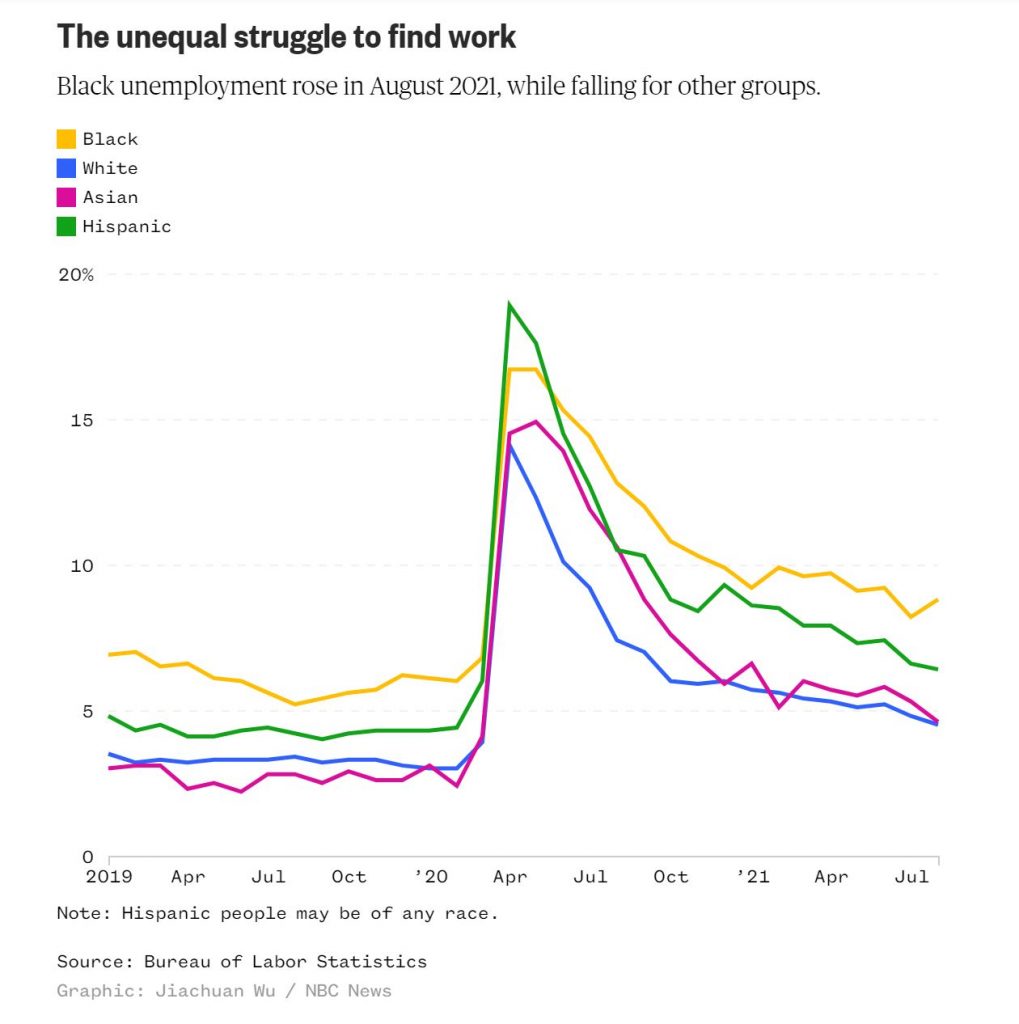

Black workers were the only racial or ethnic group whose unemployment rate increased overall in August.

JACKSON, Miss. — As the delta variant crept through Mississippi this spring, Ashley Brown kept showing up at her elderly clients’ homes, arranging their medication into pill organizers, sweeping their floors and washing their clothes.

Then she contracted Covid-19 in July, forcing her off the job for two weeks. She thought a negative test was her ticket back to a paycheck. But her shifts were reassigned while she quarantined — and when she recovered, her job was gone.

Women of color like Brown, whose mother is white and father is Black, are often likely to have low-wage jobs like home care work, which offer a critical service but lack protections, including paid sick leave and predictable schedules.

By August, what had started for Brown as a two-week pause without income threatened to stretch indefinitely. The 24-year-old mother of four started filling out applications for fast-food restaurants and a tool manufacturer. But the early-morning hours would make it all but impossible for her to arrange child care.

The career she had lost had been her best option.

“That’s the only job that works around my kids’ schedules,” she said.

More than a year after the country’s pandemic-driven recession officially ended, Brown’s struggles in Carrollton, Mississippi, illustrate how the nation’s economic recovery continues to be unequal along racial and ethnic lines.

Among the millions of unemployed Americans who sought jobs in August, prospects were particularly bleak for Black workers, who were the only racial or ethnic group whose unemployment rate increased overall. About 9 percent of Black men and 8 percent of Black women were out of work in August, an increase of about half a percentage point from July for both groups. The outlook was better for white men and women, who had the lowest unemployment rate of 4.5 percent.

The gap does not come as a surprise to economists. Even in better times, the nation’s unemployment rate has been dogged by racial disparities.

William Darity, an economist at Duke University, pointed out that Black unemployment has generally hovered at double the rate of white unemployment, since the federal government began tracking the data by race.

“It typically has held up in that way, regardless of whether the economy is in an upturn or downtown,” he said. “As a consequence, there really has never been an improvement in the Black unemployment rate that has brought it into parity with the white unemployment rate. That holds regardless of educational attainment.”

When labor markets go through rough patches, Black workers are more likely to lose their jobs first, even accounting for years of work experience and skill level. In stronger economies, their employment rates still trail the national average. The persistence of this cycle has led some economists to ask how racial bias may play a role.

“Discrimination is happening on multiple fronts,” said Kate Bahn, chief economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a nonprofit research group. “It’s happening on the downturn if you get laid off and then also, the degree to which hiring picks back up, there could also be discrimination in hiring. So that would also disproportionately harm Black workers.”

Being overrepresented in essential positions, like home health aide jobs, also increased Black workers’ vulnerability.

“They’re both facing worse opportunities because of structural racism, as well as the unique factors related to the pandemic that disproportionately put them in positions of risk in response to the public health crisis and the economy,” Bahn said.

In August, the labor force participation rate for Black workers grew, which indicates that more people were looking for jobs. The rise in unemployment signals that their demand for work was not met.

“Just because you’ve lost a job doesn’t mean that there’s one available to you that matches your skill set and pays a wage that you need to live that you could get to,” said Kristen Broady, a Metropolitan Policy Program fellow at the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit focused on public policy.