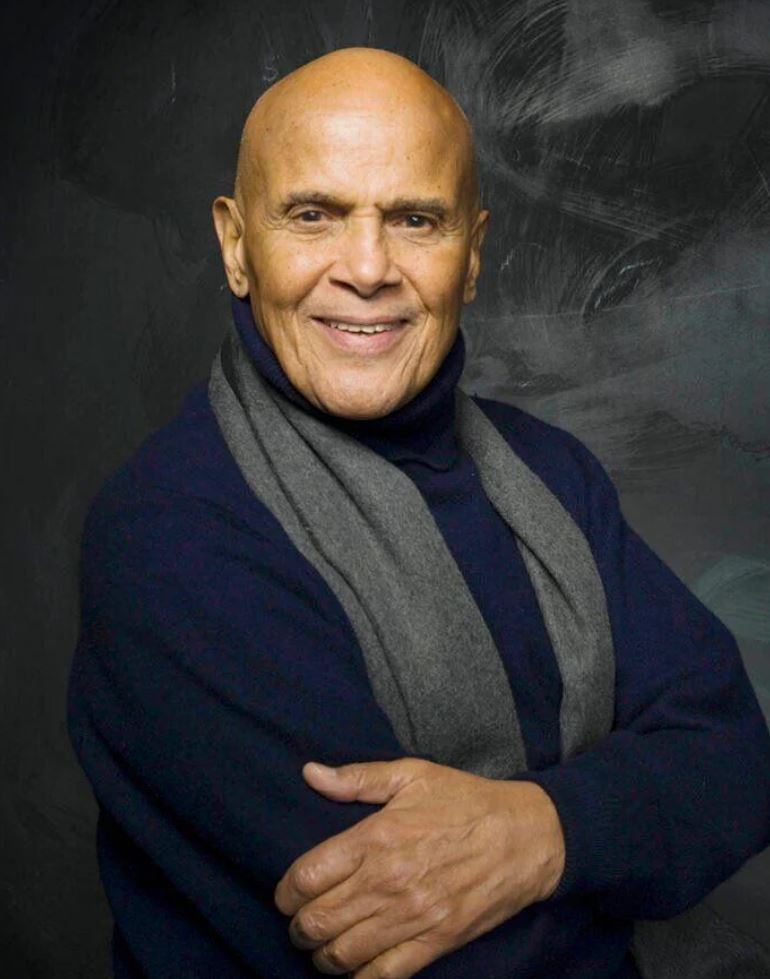

Singer and activist Harry Belafonte speaks during a memorial tribute concert for folk icon and civil rights activist Pete Seeger in New York on July 20, 2014. Belafonte died Tuesday of congestive heart failure at his New York home. He was 96. (AP Photo/Kathy Willens, file)

Harry Belafonte, activist and entertainer, dies at 96

Harry Belafonte, the civil rights and entertainment giant who began as a groundbreaking actor and singer and became an activist, humanitarian and conscience of the world, has died. He was 96.

Belafonte died Tuesday of congestive heart failure at his New York home, his wife Pamela by his side, said publicist Ken Sunshine.

With his glowing, handsome face and silky-husky voice, Belafonte was one of the first Black performers to gain a wide following on film and to sell a million records as a singer; many still know him for his signature hit “Banana Boat Song (Day-O),” and its call of “Day-O! Daaaaay-O.” But he forged a greater legacy once he scaled back his performing career in the 1960s and lived out his hero Paul Robeson’s decree that artists are “gatekeepers of truth.”

Belafonte stands as the model and the epitome of the celebrity activist. Few kept up with his time and commitment and none his stature as a meeting point among Hollywood, Washington and the civil rights movement.

Belafonte not only participated in protest marches and benefit concerts, but helped organize and raise support for them. He worked closely with his friend and generational peer the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., often intervening on his behalf with both politicians and fellow entertainers and helping him financially.

He risked his life and livelihood and set high standards for younger Black celebrities, scolding Jay-Z and Beyoncé for failing to meet their “social responsibilities,” and mentoring Usher, Common, Danny Glover and many others.

In Spike Lee’s 2018 film “BlacKkKlansman,” he was fittingly cast as an elder statesman schooling young activists about the country’s past.

Belafonte’s friend, civil rights leader Andrew Young, would note that Belafonte was the rare person to grow more radical with age. He was ever engaged and unyielding, willing to take on Southern segregationists, Northern liberals, the billionaire Koch brothers and the country’s first Black president, Barack Obama, whom Belafonte would remember asking to cut him “some slack.”

Belafonte responded, “What makes you think that’s not what I’ve been doing?”

Belafonte had been a major artist since the 1950s. He won a Tony Award in 1954 for his starring role in John Murray Anderson’s “Almanac” and five years later became the first Black performer to win an Emmy for the TV special “Tonight with Harry Belafonte.”

In 1954, he co-starred with Dorothy Dandridge in the Otto Preminger-directed musical “Carmen Jones,” a popular breakthrough for an all-Black cast. The 1957 movie “Island in the Sun” was banned in several Southern cities, where theater owners were threatened by the Ku Klux Klan because of the film’s interracial romance between Belafonte and Joan Fontaine.

His “Calypso,” released in 1955, became the first officially certified million-selling album by a solo performer, and started a national infatuation with Caribbean rhythms (Belafonte was nicknamed, reluctantly, the “King of Calypso”). Admirers of Belafonte included a young Bob Dylan, who debuted on record in the early ’60s by playing harmonica on Belafonte’s “Midnight Special.”

“Harry was the best balladeer in the land and everybody knew it,” Dylan later wrote. “Harry was that rare type of character that radiates greatness, and you hope that some of it rubs off on you.”

Belafonte befriended King in the spring of 1956 after the young civil rights leader called and asked for a meeting. They spoke for hours, and Belafonte would remember feeling King raised him to the “higher plane of social protest.”

Then at the peak of his singing career, Belafonte was soon producing a benefit concert for the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama that helped make King a national figure. By the early 1960s, he had decided to make civil rights his priority.

“I was having almost daily talks with Martin,” Belafonte wrote in his memoir “My Song,” published in 2011. “I realized that the movement was more important than anything else.”

The Kennedys were among the first politicians to seek his opinions, which he willingly shared. John F. Kennedy, at a time when Black voters were as likely to support Republicans as they would Democrats, was so anxious for his support that during the 1960 election he visited Belafonte at his Manhattan home. Belafonte explained King’s importance and arranged for King and Kennedy to meet.

“I was quite taken by the fact that he (Kennedy) knew so little about the Black community,” Belafonte told NBC in 2013. “He knew the headlines of the day, but he wasn’t really anywhere nuanced or detailed on the depth of Black anguish or what our struggle’s really about.”