The history of the Clotilda has captivated archaeologists and historians for decades. The slavers responsible for the human trafficking ordered that it be burned so that there was no evidence of the trip, since transporting slaves to the U.S. was illegal at that time. The enslaved came from the Kingdom of Dahomey, modern day Benin.

Last Slave Ship From Africa Located Off Alabama Coast

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) — Researchers working in the murky waters of the northern Gulf Coast have located the wreck of the last ship known to bring enslaved people from Africa to the United States, historical officials said Wednesday.

Remains of the Gulf schooner Clotilda were identified and verified near Mobile after months of assessment, a statement by the Alabama Historical Commission said.

The wooden vessel was scuttled the year before the Civil War to hide evidence of its illegal trip and hasn’t been seen since.

“The discovery of the Clotilda is an extraordinary archaeological find,” said Lisa Demetropoulos Jones, executive director of the commission. She said the ship’s journey “represented one of the darkest eras of modern history,” and the wreck provides “tangible evidence of slavery.”

In 1860, the wooden ship illegally transported 110 people from what is now the west African nation of Benin to Mobile, Alabama. The Clotilda was then taken into delta waters north of the port and burned to avoid detection.

The captives were later freed and settled a community that’s still called Africatown USA, but no one knew the location of the Clotilda.

A descendant of one of the Africans who was brought to the South aboard the ship said she got chills when she learned its wreckage had been found.

“I think about the people who came before us who labored and fought and worked so hard,” said Joycelyn Davis, a sixth-generation granddaughter of African captive Charlie Lewis. She added, “I’m sure people had given up on finding it. It’s a wow factor.”

A Mobile-area news reporter discovered wooden remains of what was initially suspected to be the Clotilda, but the wreck turned out to be that of another ship. That publicity helped spark a renewed search last year that found another wreck now identified as the slave ship.

Officials didn’t say how much of the ship remains or what might become of its remnants. But the dimensions and construction of the wreck match those of the Clotilda, the commission said, as do building materials including locally sourced lumber and metal pieces made from pig iron. There are also signs of fire.

“We are cautious about placing names on shipwrecks that no longer bear a name or something like a bell with the ship’s name on it,” maritime archaeologist James Delgado said in a statement. “But the physical and forensic evidence powerfully suggests that this is Clotilda.”

Officials said they are working on a plan to preserve the site where the ship was located.

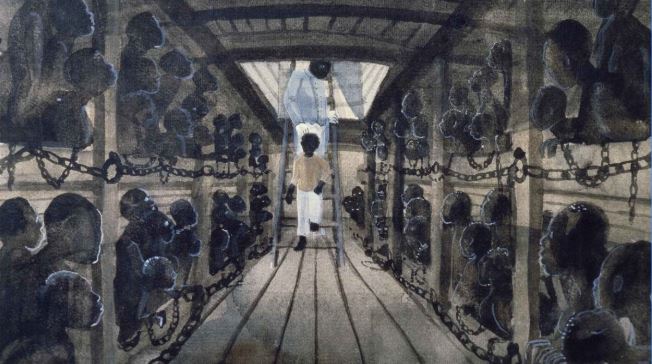

The United States banned the importation of slaves in 1808, but smugglers kept traveling the Atlantic with wooden ships full of people in chains. Southern plantation owners demanded workers for their cotton fields.

With Southern resentment of federal control at a fever pitch, Alabama plantation owner Timothy Meaher made a bet that he could bring a shipload of Africans across the ocean, historian Natalie S. Robertson has said. The schooner Clotilda sailed from Mobile to western Africa, where it picked up captives and returned them to Alabama, evading authorities during a tortuous voyage.

“They were smuggling people as much for defiance as for sport,” Robertson said.

The Clotilda arrived in Mobile in 1860 and was quickly scuttled north of Mobile Bay. It was there that researchers worked to identify the shipwreck.

The Africans spent the next five years as slaves during the American

Civil War, freed only after the South had lost. Unable to return home to Africa, about 30 of them used money earned working in fields, homes and vessels to purchase land from the Meaher family and settle in a community still known to this day as Africatown.

Officials said they plan to present a report on the findings at a community center in Africatown next week.